China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is spurring a construction boom, not just in Asia, but in parts of Europe as well. And lawyers in the PRC and beyond are poised to reap the benefits from the increased flow of work.

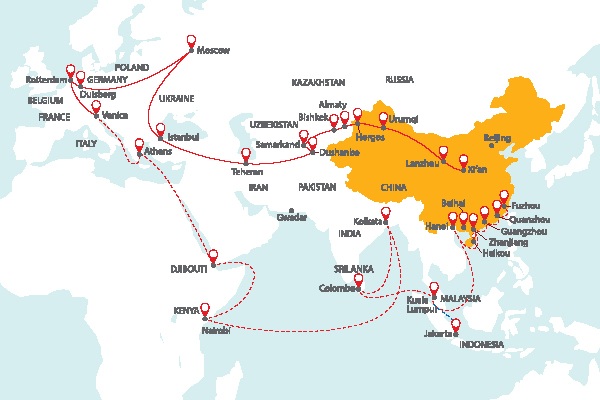

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a development strategy proposed by the Chinese government that focuses on connectivity and cooperation between China and countries across Europe and Asia.

And Chinese enterprises have been very active in infrastructure projects in these countries. According to data from the State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, 47 central state-owned enterprises (SOEs) participated or invested in the construction of 1,676 projects throughout Belt and Road countries between 2013 and 2016.

“To date, Chinese contractors have been most active in Belt and Road infrastructure projects, both primary infrastructure and now increasingly in secondary infrastructure and services as well,” says Hew Kian Heong, a partner at the Shanghai office of Herbert Smith Freehills.

“However, given the vast scale of the initiative, there is ample opportunity for construction companies outside of China to also get involved and we are seeing increased interest from Australian, European, Japanese and Korean contractors, with both Japan and Korea being China's biggest competitors,” Hew adds.

Between October 2013 and June 2016, there were 38 large-scale transportation infrastructure projects undertaken by Chinese SOEs, which included 26 countries along the Belt and Road.

There were also 40 major energy projects covering power stations, power transmission and the transmission of oil and gas, signed and carried out overseas. Those projects involved 19 different countries along the BRI.

By 2020, the overseas turnover associated with these investments will account for more than 20 percent of the total turnover of China's SOEs.

A construction boom that has gripped Asia for some time is likely to continue, led by Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam. And in all those cases, money from China and lawyers with links to China are likely to play a big part.

In a recent report, economics consultancy Oxford Economics says those countries will lead the way in the construction boom that is expected to last for at least the next decade. Construction investment in Asia is expected to average $1.61 trillion per year over the next five years. This figure is double the expected $697 billion that the United States is likely to spend or the $890 billion that will be spent in the European Union.

WIDENING THE REACH

Even though Southeast Asian countries will be the primary hotspots, the region will not be the only place likely to experience a burst of construction activity.

Hew says both Russia and the Middle East will likely be busy areas as well.

“These regions are home to clusters of projects and transport hubs that will pave the way for secondary investment and business development,” he notes.

Meanwhile, Nancy Sun, senior partner at Dentons, thinks that Central and Eastern Europe are key locations for infrastructure projects.

“Over the past five years, the investment of Chinese companies in the 16 Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries increased from $3 billion to over $9 billion in cumulative terms,” says Sun.

According to Big Four accounting firm Deloitte and the Bank of China, bilateral trade between China and CEE countries rose from $43.9 billion in 2010 to $58.7 billion in 2016, accounting for 9.8 percent of the total China-Europe trade.

“A number of iconic infrastructure projects participated by Chinese companies have begun to operate in CEE regions, such as the Belgrade bridge over the Danube having been completed and opened to traffic, and the thermal power plant in Bosnia and Herzegovina having been connected to the grid,” says Sun. “Projects on infrastructure connectivity, including Hungary-Serbia Railway and China-Europe Land-Sea Express Line, are making steady progress as well.”

Despite the continued political and economic turmoil in Western Europe, CEE regions have achieved positive economic growth of 3 percent in the past two years. Further infrastructure will be needed to support that growth.

Sun believes policy support, such as the establishment of the 16+1 cooperation, is essential to expanding trade exchanges and cross-border cooperation between China and the 16 CEE countries.

In November 2017, China and the CEE countries also formulated cooperation guidelines to emphasise their willingness to continue to discuss, build and share Belt and Road based on “16+1 cooperation.”

“Emphasis is placed on promoting the alignment of BRI with major initiatives like the European Investment Plan and national development plans of the countries, particularly the infrastructure connectivity between CEE countries and countries along the Belt and Road,” Sun says.

OPPORTUNITIES IN CHALLENGES

The BRI is also generating substantial opportunities for law firms.

Herbert Smith Freehills claims it has already captured a healthy amount of Chinese project and investment work generated by the BRI.

“We've advised on over 30 investments and projects related to the initiative in the last four years. Our Belt and Road team, comprising more than 80 lawyers globally, assists Chinese and non-Chinese clients alike. Our track record in the initiative so far, and relationships with key players, helps us advise newcomers to the Belt and Road particularly effectively,” says Glynn Cooper, partner at Herbert Smith Freehills’ Kuala Lumpur office. “As more and more projects move from planning to construction, that institutional knowledge will become ever more valuable.”

Complex infrastructure projects in developing and emerging markets always carry significant political, legal and regulatory risks.

“Every country has its own legal framework, with some less developed than others. Each industry also has its own regulatory and technical framework that demands specific specialist advice, including but not limited to legal advice,” Hew says.

By way of example, Sun pointed to the complexities that contractors face.

“There are many challenges in managing these infrastructure projects,” Sun says. “For example, for the main contractor of an infrastructure project, the owner in many cases expects the contractor to provide the financial support for the project.”

“It is not only a commercial challenge requiring the contractor to be capable in bringing in fund for the project, but also a legal challenge on how to align the governing law and other legal arrangements in the financial agreement with those in the project documentation,” Sun says.

She believes many might be unfamiliar with the legal environment of the target countries and may lack in-house talent able to coordinate projects, especially when there are multi-jurisdictions involved. It is at this stage that it is critical to engage a capable firm to assist from an early stage.

“As an example, a private company in Jiangsu Province invested in a photovoltaic power plant project in Germany. The project didn’t work out due to defects in decision-making and project management. There was a shortage in the capital chain and the investment could not be recouped,” Sun says.

“When this company invested abroad, it didn’t have a team that understood how to operate such an investment in international markets, but simply engaged a local German law firm to help it handle the investment,” Sun says. “The contracts and legal documents signed by the company were all in German, making it difficult or even impossible for the project team of the company to understand. The investment put into the project is nearly 50 million yuan ($7.8 million), and it is hard to get it back.”

Given how complex and spread out these projects can be, lawyers emphasise the importance of having a wide network of offices in Asia.

“The clients are very much happy to have an international firm like us who has more than 170 offices across 68 countries and regions to provide local knowledge and support at any time they need and also understand their needs very well through our Chinese lawyers who normally have been working with them for years as legal retainers. The clients rely on us and trust our capability of leveraging the global resources and the professional work done by both Chinese and our foreign colleagues,” Sun says.

“Our offices in Asia, namely Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Bangkok, Tokyo and Seoul, work in close collaboration with our China offices in Beijing and Shanghai. This is very important because it allows our lawyers to support our Chinese clients from both ends, in China and their project teams on the ground,” Cooper says. “As more and more projects move from planning to construction, that institutional knowledge will become ever more valuable,” he adds.

To contact the editorial team, please email ALBEditor@thomsonreuters.com.